Emotet, in general, is a banking trojan. Identified in-the-wild for the first time in 2014 as a stealth info stealer (mainly targeting banking informations), emotet has evolved to a sofisticated trojan over the years; Now having funcionalities that goes from simply keylogging to self-spreading (as worms do).

The main campaign of the malware is through malspam. Using the “urgency” pretext, emotet make his victims by malicous documents with a macro embedded, malicious scripts or malicious links. Then, the pretext comes with subjects like: “Your Invoice”, “Payment Details” or an upcoming shipment from well-known companies.

Emotet uses some tricks to evade and prevent his detection and analysis. The malware will check for common malware analysis tools (like IDA or Wireshark), check if it is running on a virtual environment and remain sleep, and every sample comes packed or encrypted.

Today we will be covering the unpacking of a sample from emotet family.

Reconnaissance

sha256: 3a9494f66babc7deb43f65f9f28c44bd9bd4b3237031d80314ae7eb3526a4d8f

md5: ca06acd3e1cab1691a7670a5f23baef4

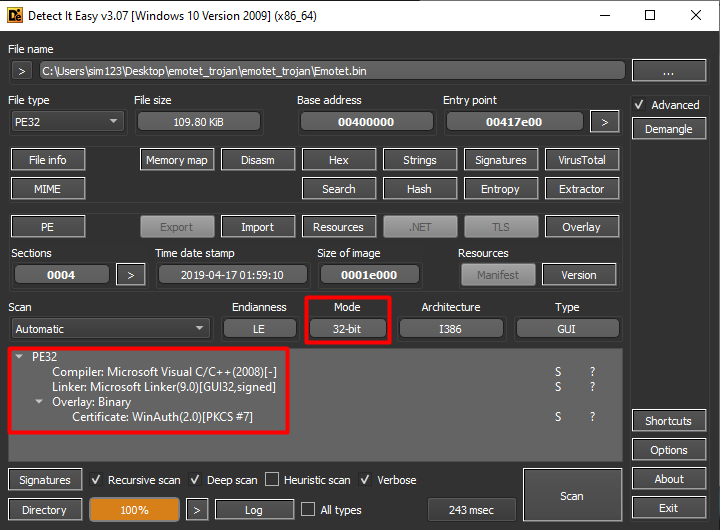

First, we need to know if the sample is definitely packed. Lets open it on DiE.

We can see that it is a 32-bit binary, made in C/C++ and having a certificate stored in the overlay section (WinAuth(2.0))

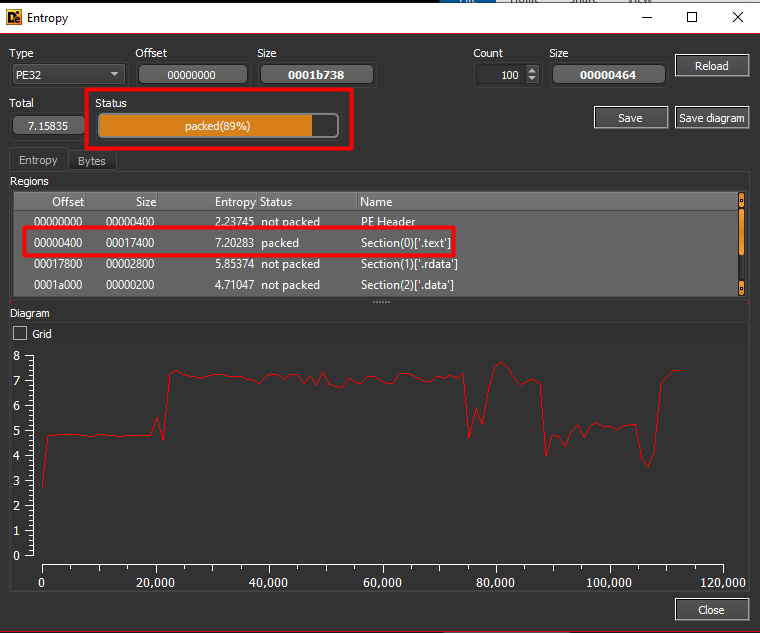

Looking at the entropy, we see that the binary has 89% chance of being packed.

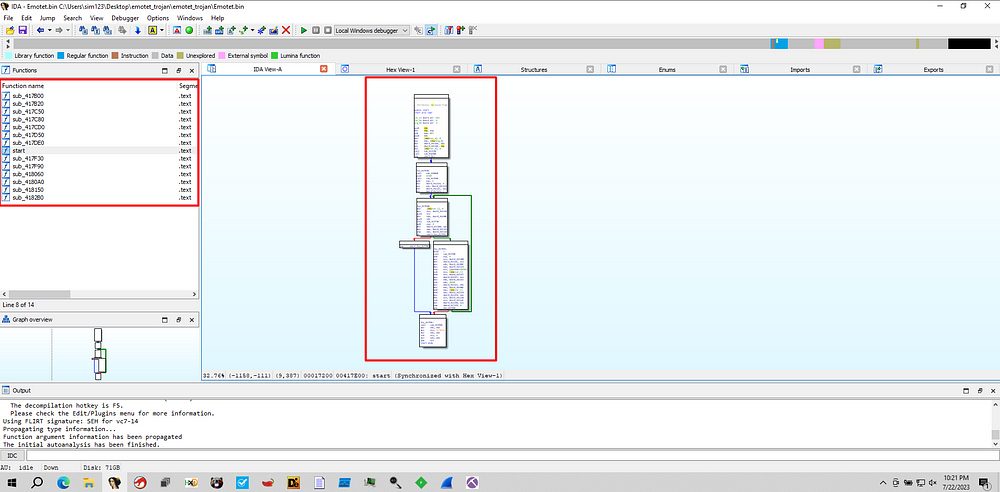

We can confirm it by looking at the sample on IDA.

IDA shows some indicators of packing, like:

- Lack of subroutines on a malware this sofisticated.

- Lack of internet-related APIs

- Main (start) function seems small and doesn’t have any WindowsAPI or indirect calls.

But, we can have the proof of it by looking into common packing APIs:

- CreateProcessInternalW()

- VirtualAlloc()

- VirtualAllocEx()

- VirtualProtect() / ZwProtectVirtualMemory()

- WriteProcessMemory() / NtWriteProcessMemory()

- ResumeThread() / NtResumeThread()

- CryptDecrypt() / RtlDecompressBuffer()

- NtCreateSection() + MapViewOfSection() / ZwMapViewOfSection()

- UnmapViewOfSection() / ZwUnmapViewOfSection()

- NtWriteVirtualMemory()

- NtReadVirtualMemor

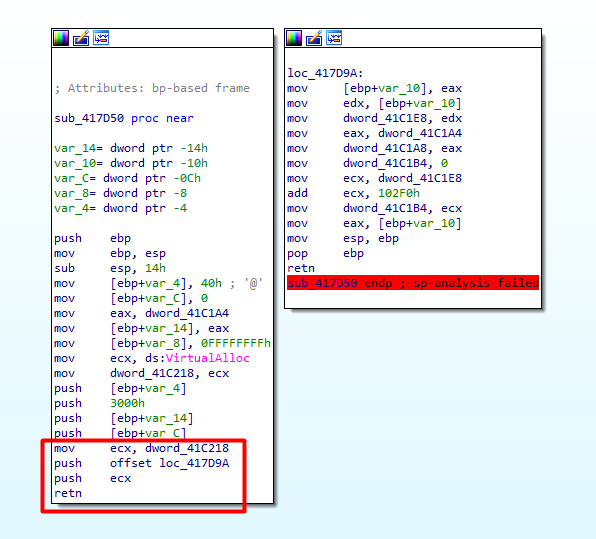

Searching for VirtualAlloc(), we will soon find the subroutine that probably is the responsible for unpacking the malware.

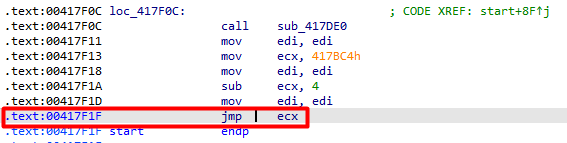

Now it gets a little bit more complicated. The red box marks an “abnormal epilogue”. An “abnormal epilogue” occurs when we have some pushes into the stack and not a single pop before it returns.

You can notice that ds:VirtualAlloc is being moved into ecx, then ecx is pushed onto the stack and the return is called, meaning the call of VirtualAlloc().

After calling ecx (VirtualAlloc), the return will execute the second push from the stack (osffset loc_417d9a), executing whatever is present on the second block, and then the real return will come.

Normally, after the code finishes the unpack, we will have a indirect call to it.

We can confirm it by looking at the end of the main function, which has an “jmp ecx”.

Again, take notes of the address. 0x00417F1F.

Unpacking

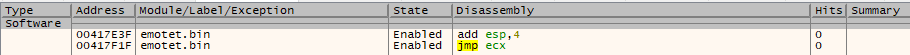

So we got two addresses to set breakpoints in:

0x00417E3F

0x00417F1F

We can open it on x64dbg, search for those addresses (Ctrl+G), and then set the breakpoints.

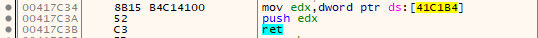

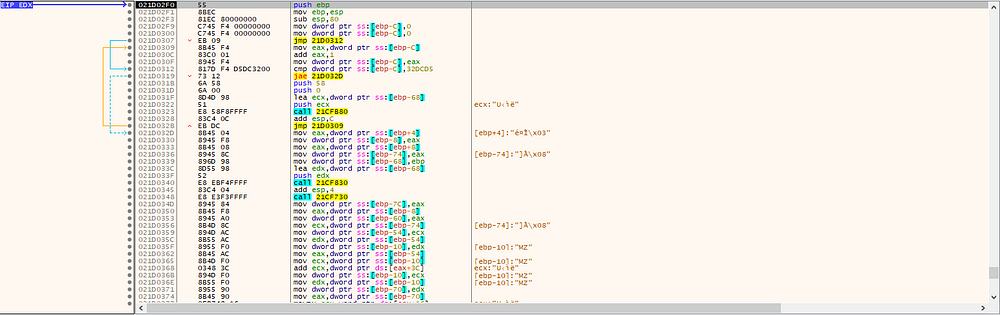

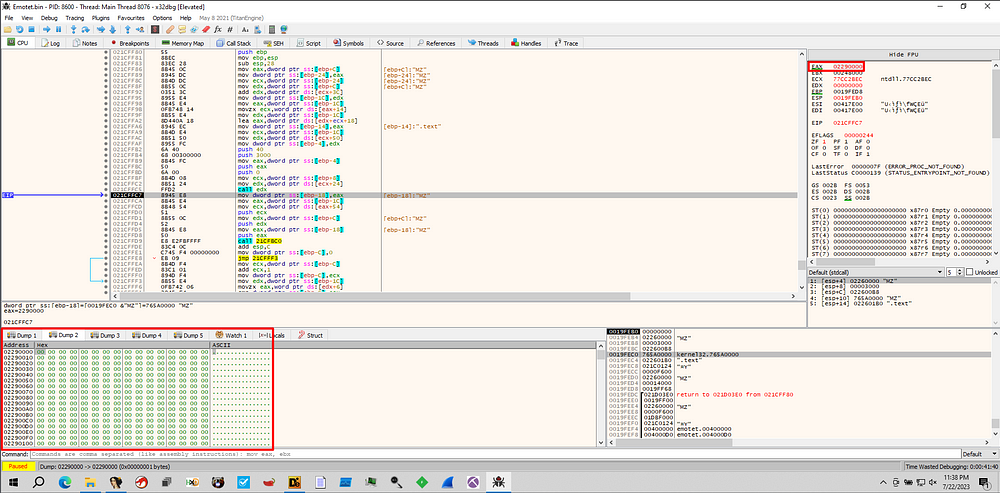

By going to the “jmp” breakpoint and scrolling down, we will encounter another abnormal set of instructions. This time, a subroutine is being pushed into the stack and not popped, the the ret makes the call to that subroutine.

Following it on the dump, we can see that it is the newly allocated memory.

Having the knowledge of the abnormal epilogue, we will stepover until the ret is called and take us to another stage of the unpack.

Now, we will have to stepover that code and analyze all those calls(e. g. call 21CF710).

After some analysis, we eventually will find the call to 3AF830, which has some interesting code:

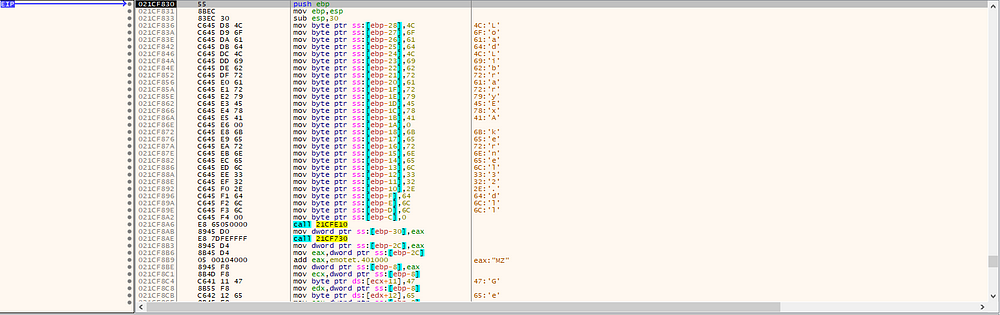

We can see that this subroutine is using “stack strings” as a form of evasion/obfuscation. This piece of code tries to obfuscate the passing of arguments “LoadLibraryExA” and “kernel32.dll” to the call 21CFE10. And many others.

As we know what is happening here, lets go straight to the return of that subroutine.

After returning to the main unpacking subroutine, we notice that the upcoming calls has the same mechanism as 3AF830.

But, the last one is important. Since the code inside of it is different, is worth a analysis.

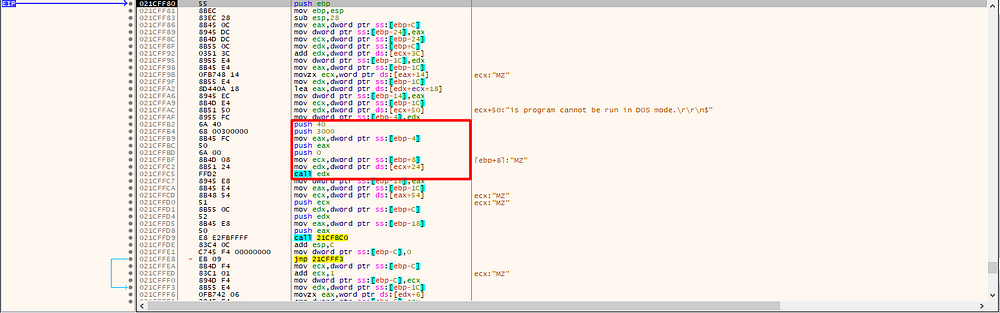

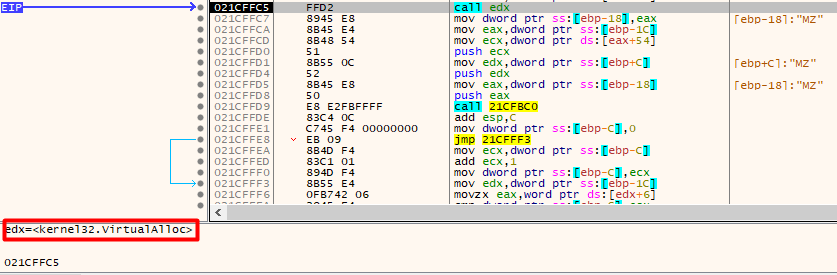

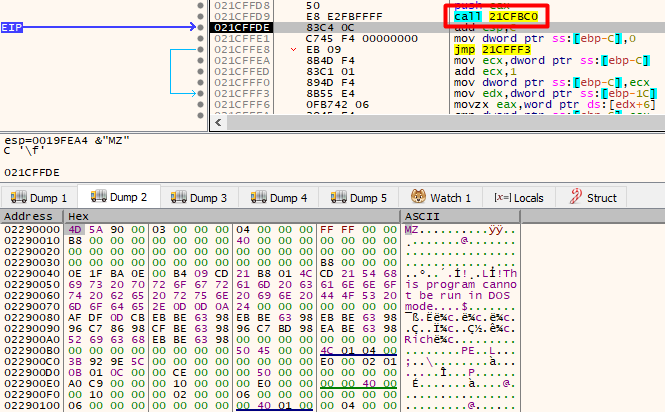

We can assume that edx is a call to VirtualAlloc, because some of the parameters passed to it are common parameters passed to VirtualAlloc itself.

push 40 as: PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE (flProtect) && push 3000 as: MEM_COMMIT / MEM_RESERVE

To confirm it, we stepover to that call.

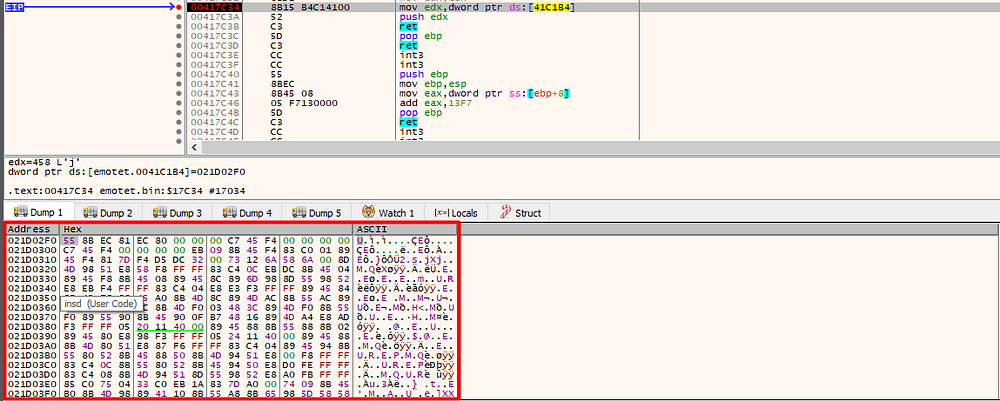

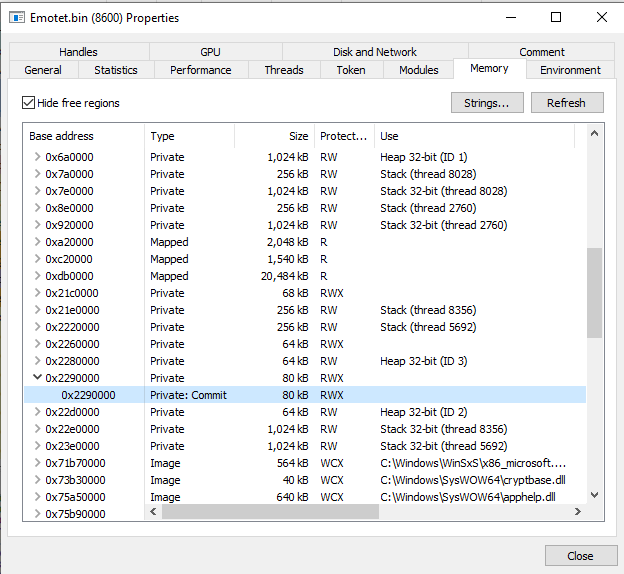

Knowing the return of that API is the base address of the recent allocated memory, we can follow the address in EAX (return).

After stepping over a little bit more, we will notice that memory being populated, more specifically after the call to 21CFBC0.

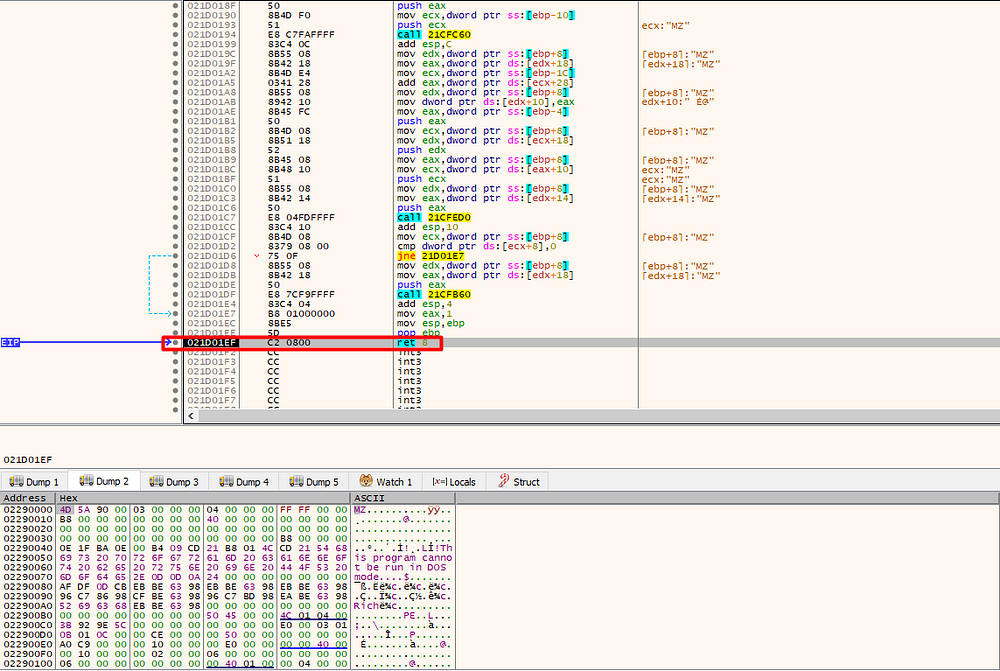

Then, we have to continue to stepover until the subroutine finishes populating that memory.

We will know it finished when we encounter a return.

After all of this, we can finally dump that memory.

The dump is made by:

right-clicking the first byte -> following it on memory map -> right-click > dump memory to file

Another way of doing it is: Opening the process in process hacker (administrator), searching for the address marked in dump, then dumping to a file.

Unmapping

If we open the recently dumped file on IDA for example, it will be completely scrambled. The reason for this is because the binary may be unaligned or mapped, so we need to align and unmap it.

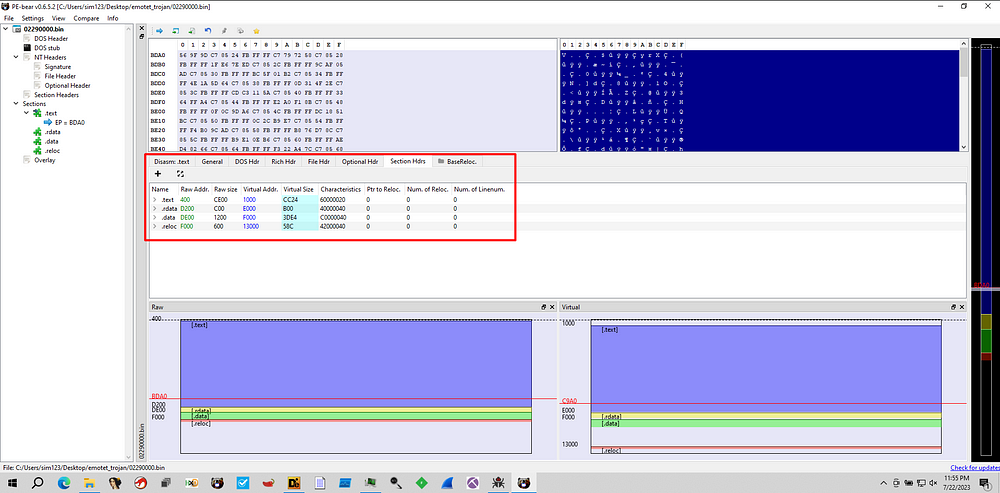

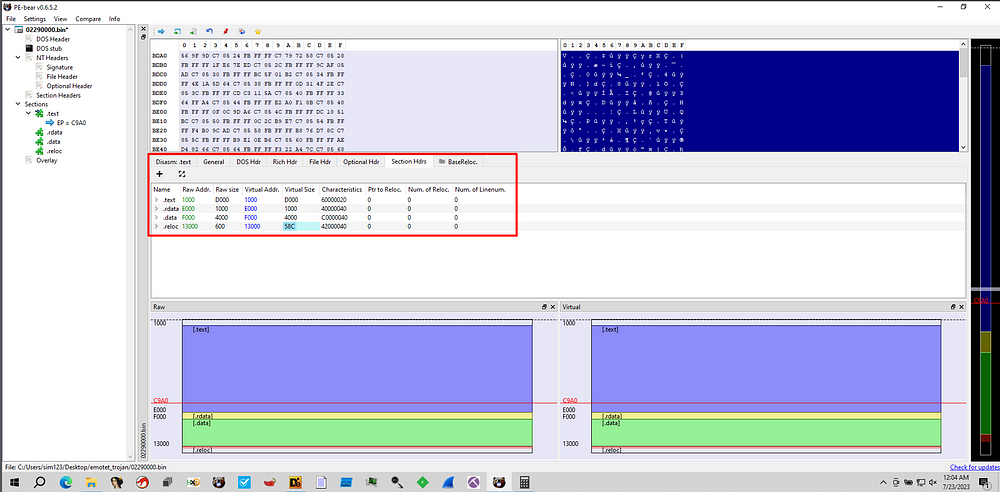

To align and unmap it, we will open the dumped binary on PE Bear.

As you can see, we don’t have the import tab, meaning we need to unmap the binary.

The unmap process is simples. It will take 4 steps:

- Change the Raw Address to the same as Virtual Address.

- Ajust the Raw Size by subtracting the first sectin by the second, and so on.

- Copy the adjusted Raw Size to the Virtual Size.

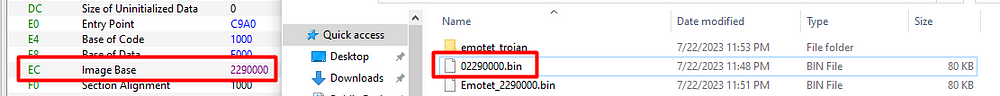

- Fix the Base Address in the Optional Header (The same as the dump address).

You can subtract those values with the windows calculator and the “programmer” option.

After that, we have the Unmapped Binary:

Now, all we have to do is save the new binary.

Binary name -> right-click -> Save the executable as...

Confirming

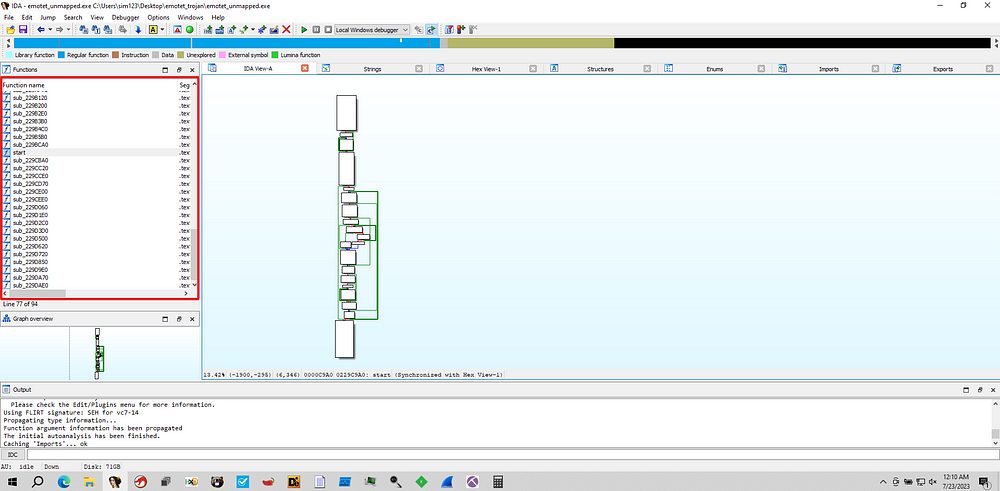

To confirm all we’ve done , let’s open it on IDA.

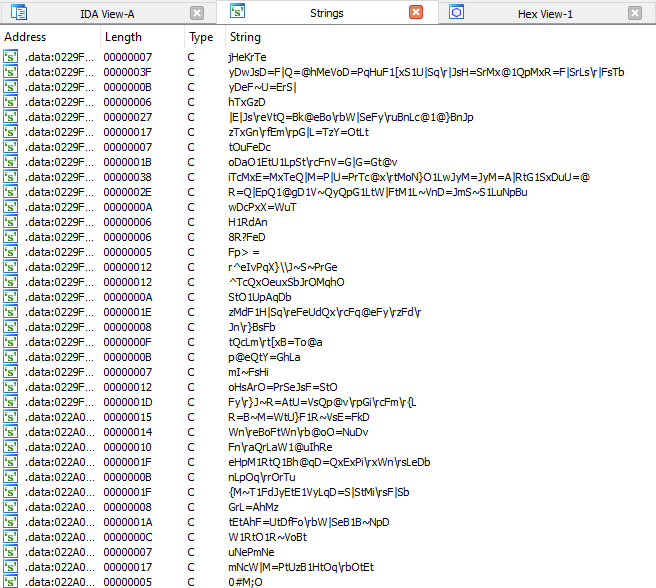

As you notice, now we have plenty of functions to analyze, and assuming by it’s strings and imports, the malware is unpacked but has a severe method of encryption and dynamic linking.

And that’s it for today, hope you liked and learned something from this article. Thank you!!!